Written by Nicholas Fuqua, Ph.D., Architectural Historian for Raba Kistner

Every year, May is National Preservation Month. Preservation Month brings awareness to historic preservation efforts throughout the country and showcases the rich and diverse architectural heritage of the United States. This year, the National Trust for Historic Preservation theme is “People Saving Places.” Historic preservation can’t happen without dedicated professionals and a community engaged in learning about the places that matter to them. Historic preservation is more than simply preserving buildings, it is cultural literacy—understanding the social, economic, and political forces that create the built environment. It goes beyond just architectural style or date of construction but encompasses the history of the people who built and used buildings and landscapes and the complex cultural contexts that shaped them.

The preservation movement in the United States began with groups of largely wealthy and mostly white women banding together to save the disappearing architecture of America’s colonial and early 19th-century past. Organizations like the Mount Vernon Ladies Association, that worked to save the home of George Washington in 1853, focused on the places associated with the founding fathers of the nation.

In the early 20th century, the preservation of cities like Charleston, New Orleans, and San Antonio were largely women-led and focused on high-style early American architecture associated with elite historical figures and the nation’s English, French, and Spanish colonial past. In San Antonio, the Conservation Society was established in 1924 and, like other early preservation groups, was composed largely of white women interested in preserving the city’s Spanish Colonial past. Buildings like the Spanish Governor’s Palace (which actually had been the home of the captain of the Presidio) and the missions were the focus of their efforts.

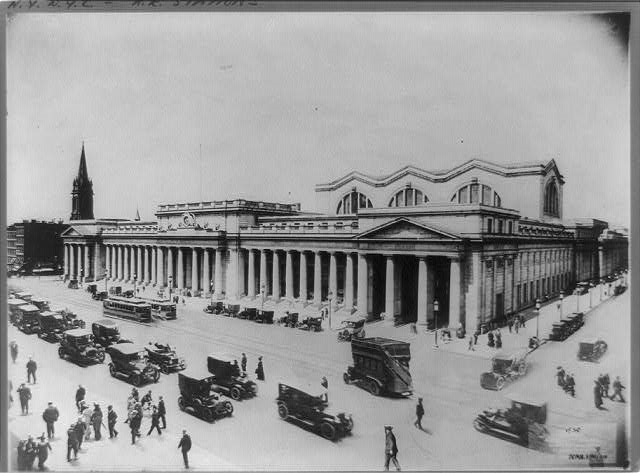

During the middle of the 20th century high profile demolitions like the destruction of Penn Station in New York City alerted the broader public of the threat to the country’s architectural and cultural heritage. This led to the passing of legislation such as the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966.

Today the preservation movement has evolved to include all of the complex cultural threads that have shaped the unique and varied cultural landscapes of this country. Places that have long been overlooked are now included in the historical narrative. Whether it’s the preservation and interpretation of the housing of enslaved people, the acknowledgement of the contributions of America’s diverse immigrant communities, or the identification of places of importance in the LGBTQIA+ community, historic preservation is beginning to embrace the full picture of American history and the many groups of people that contributed to its development.

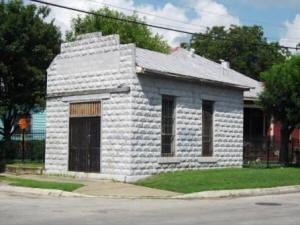

In San Antonio groups like the Esperanza Peace and Justice Center and the San Antonio African American Community Archive and Museum (SAAACAM) work to include the histories of the historically marginalized east and west sides of the city into the broader historical narrative of the city. Efforts to preserve structures like shotgun cottages, tienditas, and neighborhood landscapes have broadened the scope of what “historic” means and what buildings and spaces are deemed to be important.

Raba Kistner is proud to be involved in projects that help to protect the historic built environment and honor the communities that produced them.